History

In 1749, an acre of land outside of the settlement of Halifax was designated a burying ground. The first grave was dug on June 21st, 1749. It was a public cemetery that received burials from people of all faiths, and its capacity would soon be tested after a typhoid epidemic broke out in the winter of 1749-50, when over a thousand settlers died due to the disease. With this obvious threat to public health, the Governor Edward Cornwallis ordered that “All householders were to notify deaths within twenty four hours to one of the clergymen, under pain of fine and imprisonment. Persons refusing to attend and carry a corpse to the grave when ordered by a justice of the peace were to be struck off the ration list and sent to prison."

The size of the cemetery was increased from 1 acre to 2.25 acres in 1762.

The land on which the cemetery sat was owned by the Crown, but the Church (incorporated as the Church of St. Paul’s in 1759) was responsible for recording the burials and for maintaining the grounds. The church needed income, however it could not charge burial fees for the cemetery as it did not own the grounds. At a meeting on March 31st, 1777 they declared "that every person of whatsoever denomination who shall order the church bell to be tolled for the funeral of any deceased relation or friend, shall pay towards the expenses of the repairs of the church five shillings, and also, that all strangers who shall choose that their deceased relation or acquaintance shall be buried in the enclosed burying ground, shall pay towards the expenses of keeping the said ground, the sum of ten shillings."

On the 17th of June, 1793, the land on which the Burying Grounds sat was transferred from the Crown to the Church of St. Paul’s, finally allowing for the church to charge burial fees. This didn’t stop the citizens of Halifax from viewing it as their nondenominational town cemetery, even though it didn’t belong to the Crown anymore.

In 1801, St. Matthew’s Church received a communication from St. Paul’s that reads as such:

"...and whereas doubts have been suggested whether the rights of the Protestant Dissenters from the Church of England to be buried in the said ground commonly called the Old Burying Ground on payment of the like fees as are now paid for the burial of any of the parishioners of the said Parish Church of Saint Paul ... we, the said Rector, Church Wardens and Vestry for the time being of the said Parish Church of Saint Paul, for ourselves and our successors in office, do by these Presents testify, acknowledge and declare, that the Members of the Protestant Church or Congregation of Saint Matthew in Halifax aforesaid, as well as the Protestant Dissenters from the Established Church of England, have had since the first settlement of this Town of Halifax and Parish of Saint Paul, and still have and forever hereafter shall have good right and claim to bury their dead in the said ground commonly called the Old Burying Ground, on payment of the same dues and fees to the Rector, Sexton and other Officers for the time being of the said Parish Church of Saint Paul..."

The Burying Ground was closed to burials on August 18th, 1844. In it’s 95 years of use, approximately 12,000 people were buried within it’s grounds, from parishioners of St. Paul’s and St. Matthew’s, to members of the Royal Navy and British Army.

\

The Welsford-Parker Monument

Dedicated on the 17th of July, 1860, this monument remembers two soldiers in the British Army. Major Augustus Welsford of the 97th Regiment, and Captain William Parker of the 77th Regiment. Both of these men were Nova Scotians who fought for the British during the Crimean War, and they died on September 8th, 1855 at the storming of the Redan Fortification at Sevastopol. Also known as the Sevastopol Monument, it’s not just a rare pre-Confederation memorial, but also the only large monument in the province. The sandstone used in the creation of the monument was mined from Albert County, New Brunswick. The construction was publicly funded, and with the help of a provincial grant, George Laing carved the monument and the lion that rests on top.

\

Historical Significance

There are many historical figures that were buried in this cemetery, both local and national. The oldest existing gravestone is from 1752, and belongs to that of Malachi Salter, a child. John Connor, Halifax’s first ferryman, was buried in the cemetery in 1757. The first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, and Lieutenant Governor, Jonathan Belcher was buried here in 1776.

Halifax has always been an important position from a military and naval standpoint, and that’s well reflected in some other burials here. Lieutenant Charles Thomas of the Royal Fusilier Regiment, and Lieutenant Benjamin James of the Royal Nova Scotia Regiment are buried here, both dying in 1797.

During the war of 1812, the body of the Captain of the defeated U.S.S Chesapeake, James Lawrence, was brought to Halifax and buried here. A few weeks later, an American ship sailed into the harbor flying a flag of truce, and asked for the body to be returned for a re-burial in his own country. Permission was eventually granted, and the body of James Lawrence was exhumed, to eventually be buried in Trinity Churchyard, New York. Two sailors on the victorious H.M.S Shannon were buried close to where the Welsford-Parker Monument sits today.

Major General Robert Ross, the general responsible for the capture of Washington D.C, and the burning of the White House in 1814 is also buried in this cemetery. He was killed by a sniper on September 12th, 1814, near Baltimore. His use of rockets in battle helped inspire a part of the American National Anthem, and he inadvertently gave the White House it’s name, after it was burned so badly that it had to be painted white. His grave is an above ground tomb, with a stone slab resting on top. There is writing carved into the stone slab, and it reads:

“HERE On the 29th of September 1814 Was committed to the Earth THE BODY OF MAJOR GENERAL ROBERT ROSS, WHO After having distinguished himself in all ranks as an officer IN EGYPT, ITALY, PORTUGAL, SPAIN, FRANCE & AMERICA WAS KILLED At the commencement of an Action Which terminated in the defeat and Rout OF THE TROOPS OF THE UNITED STATES NEAR BALTIMORE. On the 12th September 1814 AT ROSS TREVOR The seat of his Family in Ireland A MONUMENT More Worthy of his Memory has been erected BY THE NOBLEMEN AND GENTLEMEN OF HIS COUNTY AND THE OFFICERS OF A GRATEFUL ARMY WHICH Under his Conduct Attacked and dispersed the Americans AT BLADENSBERG on the 24th of August 1814 AND the same day VICTORIOUSLY Entered WASHINGTON THE CAPITAL OF THE UNITED STATES IN ST. PAUL'S CATHEDRAL A MONUMENT Has also been Erected to His Memory BY HIS COUNTRY.”

\

Restoration

The Old Burying Ground remained a public green space after the closing in 1844, but vandalism and the elements took their toll on the site, and by the 1980s, the site was in dire need of extensive restoration work. In 1984, a complete record was made of the site, and from 1990 to 1991, a landscaping plan was implemented and the tilted stones in the cemetery were righted. The future of the Old Burying Ground was secured in 1986, when it was declared a Municipal Heritage site. In 1988, it became a Provincial Heritage site and 3 years later in 1991, it became the first cemetery in Canada to be designated a National Historic Site.

About this location

The cemetery is surrounded by a low stone wall, with a decorative iron fence on top, dating back to 1860. The main gate is located on Barrington Street to emphasize the role of the burying ground as a green space. Inside the grounds, some stones are tightly packed, with other areas having wide open spaces, which undoubtedly used to be filled with gravestones that have since been lost to time. Over 12,000 people were recorded to have been buried here, yet less than 10% of the gravestones/grave markers survive to this day, with some having been nearly worn down to the ground. Some of the more fragile gravestones have been framed with a protective material to prevent further decay and destruction of the historic stones.

There are many informative plaques around the entrance of the cemetery, providing history, the symbolization on the graves, and the names of some of the historical figures buried here.

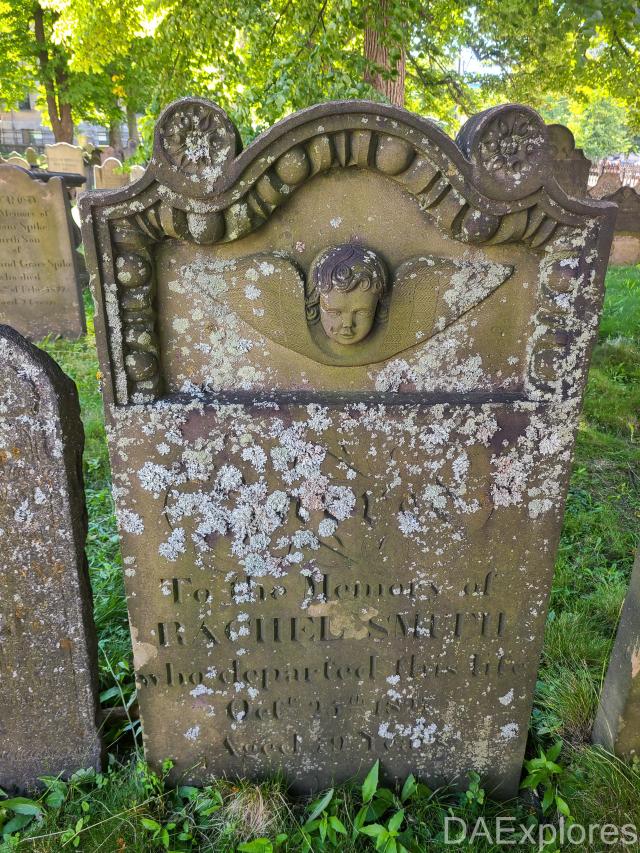

A rich variety of gravestone styles, carved images, and carving skills are visible in these aging stones, with a clear representation of how death was viewed throughout the 95 years of the cemetery’s existence visible. The older stones depict symbols of death, such as death-styled winged skulls or winged angels. A shift towards a representation of bereavement is visible in the stones from the 1800s, where the images carved into the gravestones change to funerary urns, lamps and sprigs of willow.

Albums 2

Old Burying Ground - Halifax NS

These photos were taken at the Old Burying Ground in Halifax Nova Scotia and were intended as an album to be appended to existing location # 19053 "Old Burying Ground"

5 months ago

This is a beautiful historic location in the heart of Halifax. the above description captures the site perfectly